The beginning of the suffrage movement is often cited as the 1848 Seneca Falls convention which was organized by Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott. At this meeting, attended by over 300 men and women, they drew up the "Declaration of Sentiments," intended to mirror the Declaration of Independence. While the original document is lost to this day, the suffragists used it to identify the lack of equality women had under the legal and political system. Among some of these issues were, of course, not having the right to vote, as well as divorce and custody laws, a lack of social freedoms, and employment opportunities.

Following the Seneca Falls convention, the natural question was how exactly women would attain the vote. After the 15th amendment passed, which granted voting rights to African-American men but excluded women, it became clear they would need their own amendment. Through a combination of work at both the state and national level over 70 years after the movement began, the 19th amendment was ratified on August 18, 1920. Connecticut was the 37th state to ratify the 19th amendment, on September 14, 1920.

The Connecticut Women Suffrage Association (CWSA) was formed in 1869 by Frances Ellen Burr and Isabella Beecher Hooker. Opponents, such as the Connecticut Association Opposed to Women Suffrage, argued that suffrage would only add to the "burdens" created by social progress for women. At its height in 1917, the CWSA had 32,000 members. Among those were three New Milford residents, Mary B. Weaver, Ella C. Wright and Annie Hunter Pettibone.

The following primary source documents from the collections of the New Milford Historical Society illustrate the involvement of these three New Milford women in the CWSA, along with arguments the CWSA used to convince those on the fence to support suffrage, and finally, how Mary B. Weaver used this new enfranchisement to not only vote, but to become an elected representative.

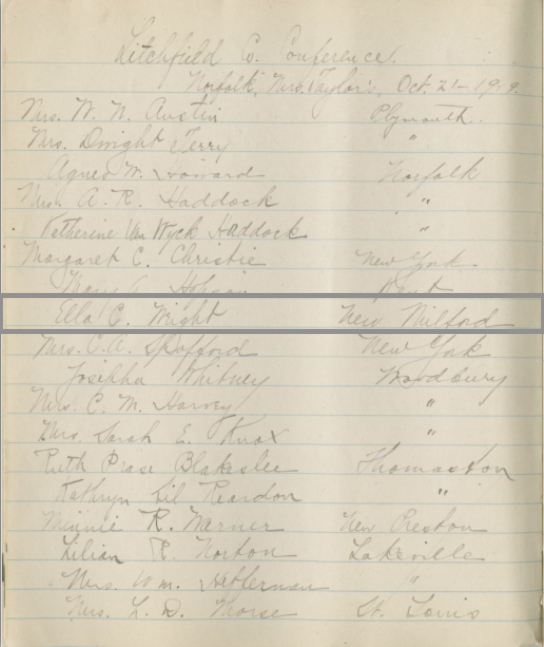

C.W.S.A., "Connecticut Woman Suffrage Association Registration Book 1919-1920," 1919. Box 3. RG 101, Connecticut Woman Suffrage Association Collection. Connecticut State Library. The names of three New Milford women, Ella C. Wright, Annie Hunter Pettibone and Mary B. Weaver, can be found registered in the records of the Connecticut Women Suffrage Association. This particular document shows that they attended the Litchfield County Conference on October 21st, 1919.

C.W.S.A., "Connecticut Woman Suffrage Association Registration Book 1919-1920," 1919. Box 3. RG 101, Connecticut Woman Suffrage Association Collection. Connecticut State Library. The names of three New Milford women, Ella C. Wright, Annie Hunter Pettibone and Mary B. Weaver, can be found registered in the records of the Connecticut Women Suffrage Association. This particular document shows that they attended the Litchfield County Conference on October 21st, 1919.

For the most part, the women involved in the movement were white and upper middle class, as these were the women who had the means and free time to dedicate to suffrage work. Ella, Annie and Mary seem to reflect this pattern. Ella was the wife of physician George Wright, Annie was married to John Pettibone, superintendent of the New Milford school system, while Mary B. Weaver would go on to serve as a State Senator.

Although only three New Milford women were formal members of the C.W.S.A., it is likely that they would have brought information about meetings and updates on the movement back to women who may not have had the ability to attend.

"The Change in the Status of Women Makes Votes For Women the Next Natural Step." Connecticut Woman Suffrage Association, 1912. New Milford Historical Society This is one of the flyers made by the Connecticut Women Suffrage Association, intended to point to the fact that women"s role in society has changed significantly throughout the last 125 years since the signing of the Constitution, and therefore their rights should reflect this change. Note that this flyer implies that women were always "mentally competent," but society had not recognized it until recent years. It should be noted that this document could be promoting some of the more exclusionary and often racist and classist suffragist rhetoric, specifically concerning how "mentally or morally incompetent" could be defined here. For example, the 1893 National Association for Women Suffrage (NAWSA) convention passed a resolution that called to attention the fact that in most states there are "more women who can read and write than all negro voters…. and foreign voters…" and if an educational requirement was added to vote, the enfranchised, educated women could outnumber those who society at large did not want to give a voice to.

"The Change in the Status of Women Makes Votes For Women the Next Natural Step." Connecticut Woman Suffrage Association, 1912. New Milford Historical Society This is one of the flyers made by the Connecticut Women Suffrage Association, intended to point to the fact that women"s role in society has changed significantly throughout the last 125 years since the signing of the Constitution, and therefore their rights should reflect this change. Note that this flyer implies that women were always "mentally competent," but society had not recognized it until recent years. It should be noted that this document could be promoting some of the more exclusionary and often racist and classist suffragist rhetoric, specifically concerning how "mentally or morally incompetent" could be defined here. For example, the 1893 National Association for Women Suffrage (NAWSA) convention passed a resolution that called to attention the fact that in most states there are "more women who can read and write than all negro voters…. and foreign voters…" and if an educational requirement was added to vote, the enfranchised, educated women could outnumber those who society at large did not want to give a voice to.

"This Dealer Givers Her No Choice." Woman"s Journal; Official Organ of The National American Suffrage Association, August 31, 1912, Vol. XLIII, No. 34 edition. New Milford Historical Society. One of the major appeals of suffrage was that it could enable women to enact social change and reform. Originally the arguments for suffrage were concerned with what the vote could do for women, and transitioned into what women could actually do for the government and the community. This political cartoon in the Woman"s Journal highlight a number of these so-called "social housekeeping" issues that women were concerned with, namely, clean streets, better factory conditions, and pure water. In her 1909 essay "Why Women Should Vote," activist Jane Addams argued that as society becomes more complicated, women had the right to extend their responsibility beyond managing their homes. For example, outside conditions, such as poor conditions at a factory her daughter may be working at that lead to disease or injury, made it impossible for her individual devotion to her family to be enough to keep them safe. Additionally, there was a significant overlap in membership between NAWSA and the Women"s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU). As New Milford had a Temperance Union of their own, it is apparent that this was one of the issues that concerned these local men and women.

"This Dealer Givers Her No Choice." Woman"s Journal; Official Organ of The National American Suffrage Association, August 31, 1912, Vol. XLIII, No. 34 edition. New Milford Historical Society. One of the major appeals of suffrage was that it could enable women to enact social change and reform. Originally the arguments for suffrage were concerned with what the vote could do for women, and transitioned into what women could actually do for the government and the community. This political cartoon in the Woman"s Journal highlight a number of these so-called "social housekeeping" issues that women were concerned with, namely, clean streets, better factory conditions, and pure water. In her 1909 essay "Why Women Should Vote," activist Jane Addams argued that as society becomes more complicated, women had the right to extend their responsibility beyond managing their homes. For example, outside conditions, such as poor conditions at a factory her daughter may be working at that lead to disease or injury, made it impossible for her individual devotion to her family to be enough to keep them safe. Additionally, there was a significant overlap in membership between NAWSA and the Women"s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU). As New Milford had a Temperance Union of their own, it is apparent that this was one of the issues that concerned these local men and women.

Mary B. Weaver, Representative for New Milford in Connecticut State Legislature. "The Feminine Element in the Connecticut Legislature: Seven Women Members." New Milford Historical Society. Suffrage opened the door for women to become legislators, and enact change at the source. By 1923, there were seven women serving in the Connecticut State Legislature. During her terms as Representative for New Milford, Mary B. Weaver followed through on the social issues that the suffrage movement had emphasized. Rep. Weaver was clerk of The Committee on Humane Institutions, and reported back on her visits to the different institutions that are under the Department of Welfare. At a meeting of the League of Women voters in 1923, Rep. Weaver reported what she saw at a hospital for children afflicted by tuberculosis at a hospital in Niantic, and a Psychiatric Home in Middletown, noting that neither had adequate conditions. She proposed a grant of $250,000 to the Yale Medical School in order to increase the number of doctors, nurses and attendants that could assist with these institutions.

Mary B. Weaver, Representative for New Milford in Connecticut State Legislature. "The Feminine Element in the Connecticut Legislature: Seven Women Members." New Milford Historical Society. Suffrage opened the door for women to become legislators, and enact change at the source. By 1923, there were seven women serving in the Connecticut State Legislature. During her terms as Representative for New Milford, Mary B. Weaver followed through on the social issues that the suffrage movement had emphasized. Rep. Weaver was clerk of The Committee on Humane Institutions, and reported back on her visits to the different institutions that are under the Department of Welfare. At a meeting of the League of Women voters in 1923, Rep. Weaver reported what she saw at a hospital for children afflicted by tuberculosis at a hospital in Niantic, and a Psychiatric Home in Middletown, noting that neither had adequate conditions. She proposed a grant of $250,000 to the Yale Medical School in order to increase the number of doctors, nurses and attendants that could assist with these institutions.

"Rep. Weaver Reports: Tells of Work Being Done In Legislature." The New Milford Times, March 29, 1923, Vol 10. edition, sec. 1. New Milford Historical Society. Additionally at this meeting, Rep. Weaver gave an informal talk on the ins-and-outs of legislative work to those in attendance, and "showed keen interest in her subject" as she answered questions. At an address to the "Monday Club," Miss Weaver said "If you have found a law that is not there it is your business to see that it is put there, if not by yourself see that someone does."

"Rep. Weaver Reports: Tells of Work Being Done In Legislature." The New Milford Times, March 29, 1923, Vol 10. edition, sec. 1. New Milford Historical Society. Additionally at this meeting, Rep. Weaver gave an informal talk on the ins-and-outs of legislative work to those in attendance, and "showed keen interest in her subject" as she answered questions. At an address to the "Monday Club," Miss Weaver said "If you have found a law that is not there it is your business to see that it is put there, if not by yourself see that someone does."

Sources:

Aileen S. Kraditor. The Ideas of the Woman Suffrage Movement/ 1890-1920. New York: W.W.

Norton & Company, 1981.

C.W.S.A. "Connecticut Woman Suffrage Association Registration Book 1919-1920," 1919. RG

101, Connecticut Woman Suffrage Association Collection. Box 3. Connecticut State

Library.

Hickox, George A. Legal Disabilities of Married Women in Connecticut. Hartford, Connecticut:

Case, Lockwood & Brainard, 1871.

Ruth McIntire Dadourian. "Fifteen Women Aid in Making Laws of State: Several Sit on

Important Committees- Some Were Opposed to Suffrage- Majority Come From Larger

Towns or Cities." The Hartford Times, February 2, 1927. Suffrage and Legislation File.

New Milford Historical Society.

"This Dealer Givers Her No Choice." Woman's Journal; Of*cial Organ of The National

American Suffrage Association, August 31, 1912, Vol. XLIII, No. 34 edition. Suffrage

and Legislation File. New Milford Historical Society.

"Chairman Hays of the Republican National Committee Receiving a Delegation from the

Connecticut Woman Suffrage Association," March 3, 1913. Suffrage and Legislation File.

New Milford Historical Society.

"History of the Year, 1919-1920." C.W.S.A., 1920. RG 101, Connecticut Woman Suffrage

Association Collection. Box 4. Connecticut State Library.

"Rep. Weaver Reports: Tells of Work Being Done In Legislature." The New Milford Times,

March 29, 1923, Vol 10. edition, sec. 1. Suffrage and Legislation File. New Milford

Historical Society.

"Woman Legislator: Miss Weaver Tells Monday Club Some Experiences." The Hartford Times,

November 22, 1923. Suffrage and Legislation File. New Milford Historical Society.

Connecticut History. "19th Amendment: The Fight Over Woman Suffrage in Connecticut,"

August 18, 2017. https://connecticuthistory.org/19th-amendment-the-*ght-over-woman-

suffrage-in-connecticut/.

National Park Service. "Connecticut and the 19th Amendment," January 15, 2020. https://

www.nps.gov/articles/connecticut-and-the-19th-

amendment.htm#:~:text=After%20decades%20of%20arguments%20for,19th%20Amendment%2

0in%20June%201919.&text=Connecticut%20was%20not%20one%20of,it%20on%20September

%2014%2C%201920.

Torrington Library. "Connecticut Suffragettes." Accessed July 16, 2020. http://

www.torringtonlibrary.org/connecticut-suffragettes.html.

"The Change in the Status of Women Makes Votes For Women the Next Natural Step."

Connecticut Woman Suffrage Association, n.d. Suffrage and Legislation File. New

Milford Historical Society. Accessed February 28, 2020.

"Women in the Home." Connecticut Woman Suffrage Association, n.d. New Milford Historical

Society. Suffrage and Legislation File. Accessed February 28, 2020.

Mary B. Weaver:

Ancestry.com. 1940 United States Federal Census [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA:

Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2012. Year: 1940; Census Place: New Milford, Litchfield,

Connecticut; Roll: m-t0627-00509; Page: 9A; Enumeration District: 3-24.

Annie Hunter Pettibone:

Ancestry.com. 1930 United States Federal Census [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA:

Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2002. Year: 1930; Census Place: New Milford, Litchfield,

Connecticut; Page: 11A; Enumeration District: 0017; FHL microfilm: 2340004

Ella C. Wright:

Ancestry.com. 1930 United States Federal Census [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA:

Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2002. Year: 1930; Census Place: New Milford, Litchfield,

Connecticut; Page: 16B; Enumeration District: 0017; FHL microfilm: 2340004.